The European Parliament and the Council of the EU are currently discussing the new EU legislative framework to counter money laundering. The European Commission had presented a comprehensive legislative package to overcome the nationally fragmented legal framework and inconsistent implementation of the existing anti-money laundering (AML) legislation in late July. The package focuses, among other issues, on coherent supervision and closer cooperation between authorities.

Meanwhile in Germany it is mainly the proposed cash limit of €10,000 that sparks discussions. This particular issue is, however, much less relevant in other Member States: in many countries, cards or mobile payments are the preferred option, even for very small amounts. In 18 out of 27 Member States cash limits are already in place, many of which have only recently been introduced. These range from €500 in Greece to around €13,700 in the Czech Republic and are often linked to further restrictions such as the possibility to decline larger cash payments or to check the payee’s identity.

Source: Commission Impact Assessment of 20.07.2021, European Consumer Centre, own research

Yet, particularly Germans – as well as Austrians – do hold on to their cash. It should therefore be no surprise that the issue is featured in several party manifestos for the upcoming Bundestag elections. The centre-right CDU/CSU, for example, refer to cash as “lived freedom” and the liberal FDP is likewise vocally opposed to such a limit.

The Greens, on the other hand, favour a “high cash limit”, while the position of the Social Democrats (SPD) remains unclear. Although there is no explicit statement on the subject in the party’s election manifesto, individual SPD financial experts have openly supported the cash limit. According to the Handelsblatt, Lothar Binding, financial policy spokesman of the SPD parliamentary group in the Bundestag, “would even have preferred a limit of no more than 5,000 euros”. To date, the German government has not taken a clear stance on the cash limit question in the first discussions of the Council of the EU, indicating disagreement within the coalition.

In the overall context of the proposed European legislative package, such focus on the cash limit proves however to be lopsided as the Commission is pairing this measure with an exclusion of traders in goods from the scope of the revised legislation – only art dealers and jewellers would be exempted. This means the AML legal framework would continue to apply to the latter, however not to other traders such as for vehicles, antiques, boats, or electronics.

Concretely speaking, the amended scope in combination with the cash limit means the following: traders in goods have hitherto only been subject to anti-money laundering rules for transactions of €10,000 or more; with the introduction of a limit at that particular amount, these traders would automatically and entirely fall outside the scope of AML rules.

Even though the logic seems reasonable in principle, the exemption of traders in goods could lead to an increase in the volume of money laundering in practice. Already today, a very high number of unreported money laundering cases is being suspected, especially in the non-financial sector (NFS) where authorities seem to have difficulties to employ effective enforcement.

At the end of 2020, an internal report of the Federal Court of Auditors (Bundesrechnungshof – BRH) issued a remarkably poor rating for anti-money laundering in the non-financial sector (NFS). Recent figures of the German Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU)’s annual report are reflecting this trend as well.

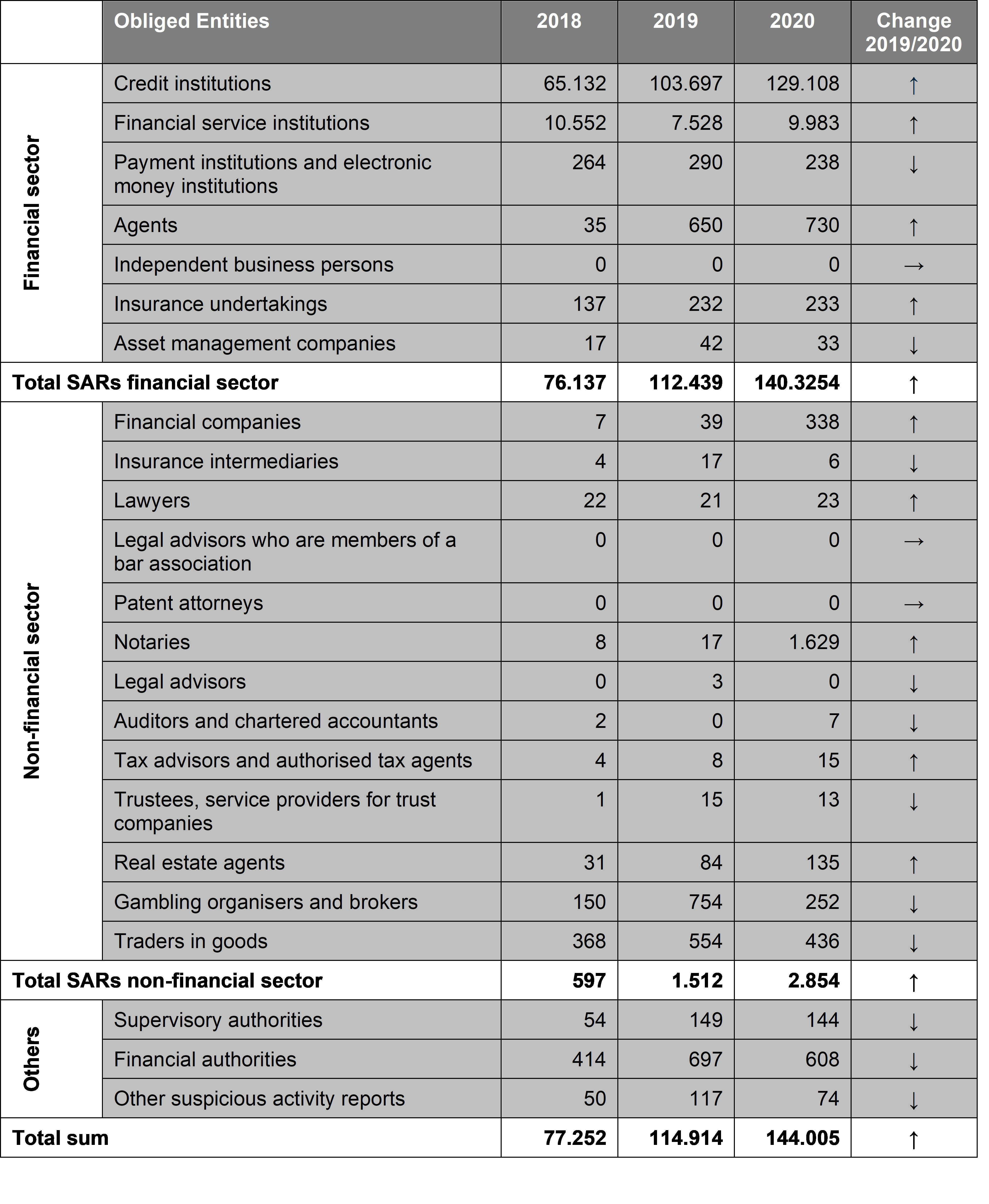

Number of suspicious activity reports (SARs) according to obligated entity groups

Source: German FIU, Annual Report 2020, own translation

According to the BRH report, the German Federal Ministry of Finance assumes 28,000 suspicious cases in the NFS per year. Yet, according to the FIU study, only 2,854 reports were submitted for this sector in 2020. Less than 1.5% of the suspicious activity reports (SARs) received by the FIU in 2018-2020 were issued by the NFS, although the number of obliged entities within is considerably higher than it is in the financial sector. In the same period, traders in goods accounted for only 0.4% of the SARs. While the traders in goods thus record the second highest number of SARs in the NFS after notaries, it still falls significantly short of the latter. This discrepancy between suspected SARs and actual SARs highlights the inefficiency of anti-money laundering supervision in the NFS.

The mere introduction of a cash limit alone would not solve these issues. Especially in the trade of goods, money launderers frequently use many smaller transactions to disguise their activities. Although the current European legislative proposal also stipulates that “linked cash transactions” may in total not exceed the threshold of €10,000, this remains difficult to track in practice.

After all, if those traders are no longer subject to legal obligations, it stands to reason that employees of, say, a small car dealership, will no longer be trained to keep a watchful eye for irregularities and will hence not be able to identify linked transactions. This may then be exploited by money launderers, putting traders in goods at risk of becoming a gateway for money laundering – even if unknowingly and without any actual responsibility on their part.

The coming months will show how the European Parliament and the Council of the EU will address the issues of cash limits and trade in goods. The evolution of Germany’s position will also remain of interest. Given the different views of the political parties mentioned above, it can be assumed that the outcome of the Bundestag elections and the subsequent coalition negotiations will define Germany’s position in this regard.

In any case, the regulatory focus is currently in Brussels, where the anti-money laundering rules for the next few years are now being laid-down. By transferring many of the elements of the previous Directives into the proposed Regulation, Member States’ room for manoeuvre in implementing the package is likely to be considerably restricted.