Just before the summer break, the European Commission presented a comprehensive legislative package to reinforce and harmonise its efforts in countering money laundering and terrorist financing.

Most notably, a new EU anti-money laundering authority is to be established with its main task being to improve cooperation between the national Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs). Already in 2019, the European Commission had identified structural deficiencies in the fight against money laundering, especially in the banking sector. Due to the recent prominent cases of money laundering in this sector, the lack of effective supervision became apparent.

According to the European Commission, these structural deficiencies are predominantly caused by the fragmentation of regulatory and supervisory rules and, to a greater extent, by the different tasks and competences of individual authorities in the implementation of those EU rules.

Politely but clearly stated, the Commission said that the supervisory measures taken by the national authorities in response to these cases “were very inconsistent in terms of their promptness and effectiveness”.

The Commission found that the Member States – and Germany in particular – had implemented a division of competences which led to “inefficient cooperation”; notably among the authorities responsible for countering money laundering, the supervisory authorities, the FIUs and the law enforcement authorities.

A new EU authority with a two-tiered approach

The Authority for Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AMLA) is to be the centrepiece of a uniform EU supervisory mechanism. It shall perform two main tasks: first, AMLA is to assume indirect supervision of the EU’s anti-money laundering efforts, and second, it is tasked with supporting the FIUs in the Member States.

As regards the first task, it would directly supervise financial institutions that face a “high inherent risk of money laundering and terrorist financing”.

The corresponding risk assessment determining such state of high inherent risk is to be carried out every three years and concerns credit institutions that are active in at least seven Member States. The benchmarks for the risk assessment include the nature of the business relationship, the products and services offered, as well as geographical factors, especially with respect to correspondent banks.

In the non-financial sector, on the other hand, the new authority is only to perform a coordinating role. This is likely to constitute a challenge for the new authority given the frequently criticised fragmentation of supervision in Germany: While in some federal states, ministries are entrusted with the supervisory task, in others it is the local regulatory authorities. Moreover, of Germany’s more than 100 supervisory authorities in the non-financial sector, only one in ten actually reported to have taken measures.

The second task of the AMLA is to support the FIUs in the Member States, inter alia, by adopting standards for reporting and information exchange, supporting joint operational analyses, and hosting the secure communication network FIU.net.

Increased reporting of suspicious activities in the financial and non-financial sectors

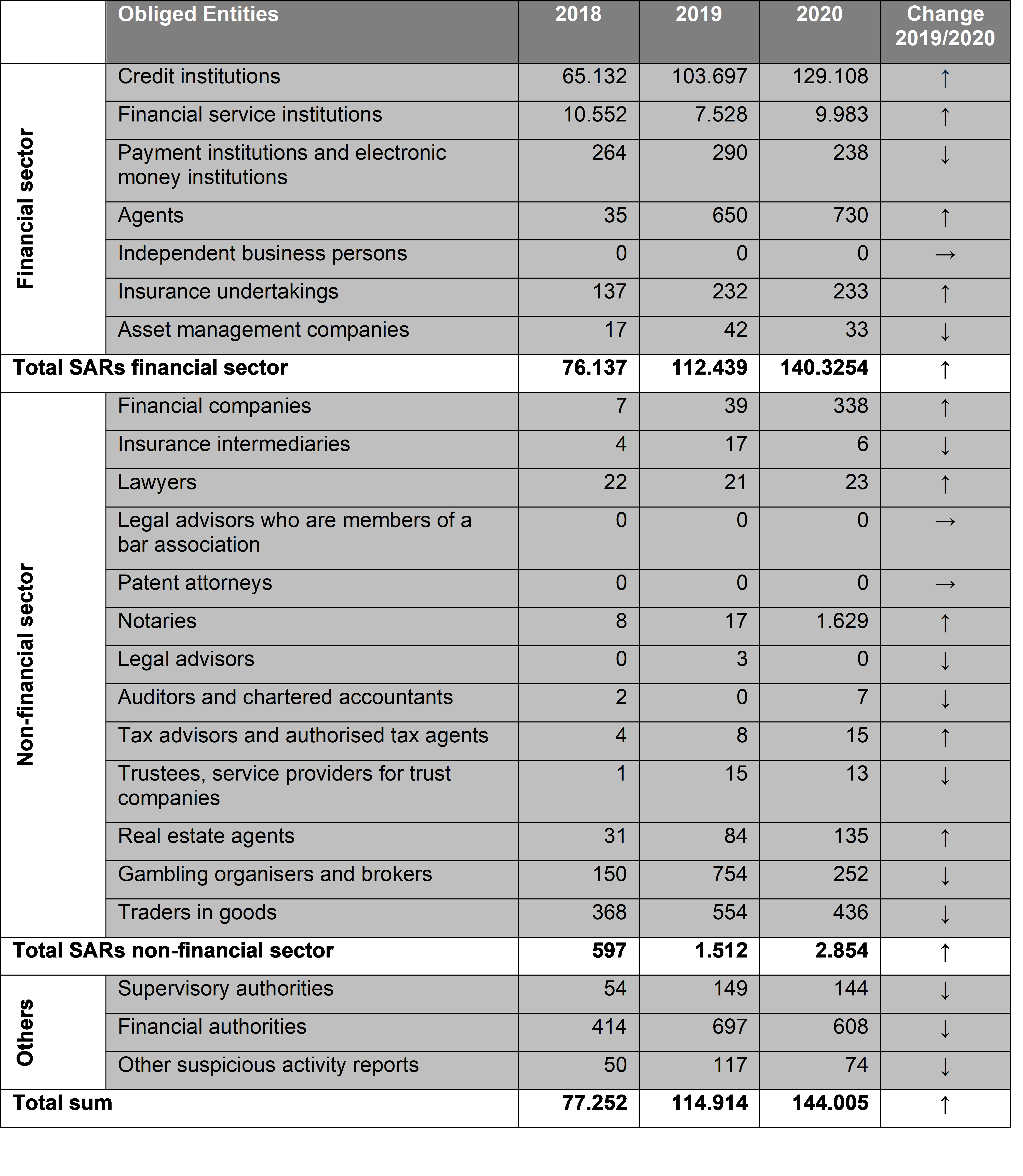

The respective number of suspicious activity reports seems to be backed up by the different sectoral approaches. According to the annual report for 2020 by the German FIU, the vast majority of reports (around 97 percent) were filed by the financial sector. While the overall reporting volume increased by about 25 per cent, the non-financial sector recorded yet another disproportionate increase of almost 90 per cent compared to 2019.

Number of suspicious activity reports (SARs) according to obligated entity groups

Source: German FIU, Annual Report 2020, own translation

Overall, the share of reports from the non-financial sector increased from solid 1.3 per cent in the previous year to just below 2 per cent now. This occurred despite the circumstance that there was a sharp decline in reports in the gambling sector and among traders in goods – which is likely to be connected to the pandemic-related closures of their premises.

Regarding the number of obligated parties to be supervised, the financial and non-financial sectors diverge less. From 2019 to 2020, the number of registered obligated parties increased from 1,862 to 2,565, of which 1,482 belong to the financial sector and 1,083 to the non-financial sector.

EU-wide harmonisation by means of standardisation

In the interest of harmonisation, it is being proposed to entrust the AMLA with competences to adopt “Regulatory Technical Standards” (RTS). Practically speaking, the new authority could thus standardise suspicious activity reports and corresponding procedures across the EU. This would considerably simplify compliance for institutions and companies operating across borders.

Thus, in both the financial and non-financial sector, the national authorities are to be complemented by a supervisor that has the capacity to adopt further instructions, if necessary.

Recently, the FDP parliamentary group in the German Bundestag posed a brief inquiry on the practical design of the new EU anti-money laundering authority towards the Federal government. Yet, it is the Commission who is providing – not all but many – answers to the FDP-questions within the respective legislative proposals and accompanying documents.

In terms of the envisaged costs and staff structure of the AMLA, the European Commission assumes in its proposal that, with the operational start of the authority in 2026, it will have a staff of about 250, with an allocated annual budget of 45.6 million euros. The establishment of the authority is scheduled for 2023 with the aim of launching direct supervision of financial institutions with high inherent risk as early as 2026, including a three-year lead time.

Negotiations are to begin before the Bundestag elections

The question as to the location of the new authority is yet to be answered. Both, Paris, as the seat of the European Banking Authority (EBA), and Frankfurt, as the seat of the European Central Bank (ECB), argue in their favour, based on their previously assigned competences in combating money laundering. The negotiations for the seat of the European Banking Authority and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) following its withdrawal from London have proven that presumed favourites do not necessarily come out on top. In this respect, it is to be seen whether the German federal government will be more fortunate this time.

Similar to the proposed “Regulation on the prevention of the use of financial system for the purposes of money laundering and terrorist financing”, the present proposal for a “Regulation establishing the Authority for Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism” does not allow for any subsequent national adjustments. The leeway which the previous five Directives provided to the Member States by means of transposition will no longer exist in the future.

The ball is thus clearly in the Brussels court now, where the deliberations have already unfolded: within the Working Group of the Council of Finance Ministers, discussions began earlier this summer while the Parliamentary Committee for Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON) started its work in early September.