The insights are based on expert interviews conducted in Brussels with members of the Council working groups on health which were published as part of a scientific article in Global Affairs Journal.

Political procedures within the European Union are primarily a matter of competence. One often associates the European Union with all the institutions located in Brussels. But it is much more an umbrella term for the European Commission. EU Member States ultimately remain sovereign states that pool their sovereignty in some policy areas – sometimes even just parts of them – in order to exert influence through joint action.

Health policy constitutes a good example. Here, the Commission has only so-called “supportive competence”, i.e. it can only support, coordinate or complement the actions of the Member States. Therefore, it is much more the Council as the (coordination) platform of the Member States within which EU health policy primarily takes place.[1].

The exertion of influence top-down vs. bottom-up

The Council meets in ten different configurations, in which the ministers of the Member States meet to amend or adopt legislation. In addition, the Council negotiates documents that do not have legal effect, such as conclusions, resolutions and declarations.

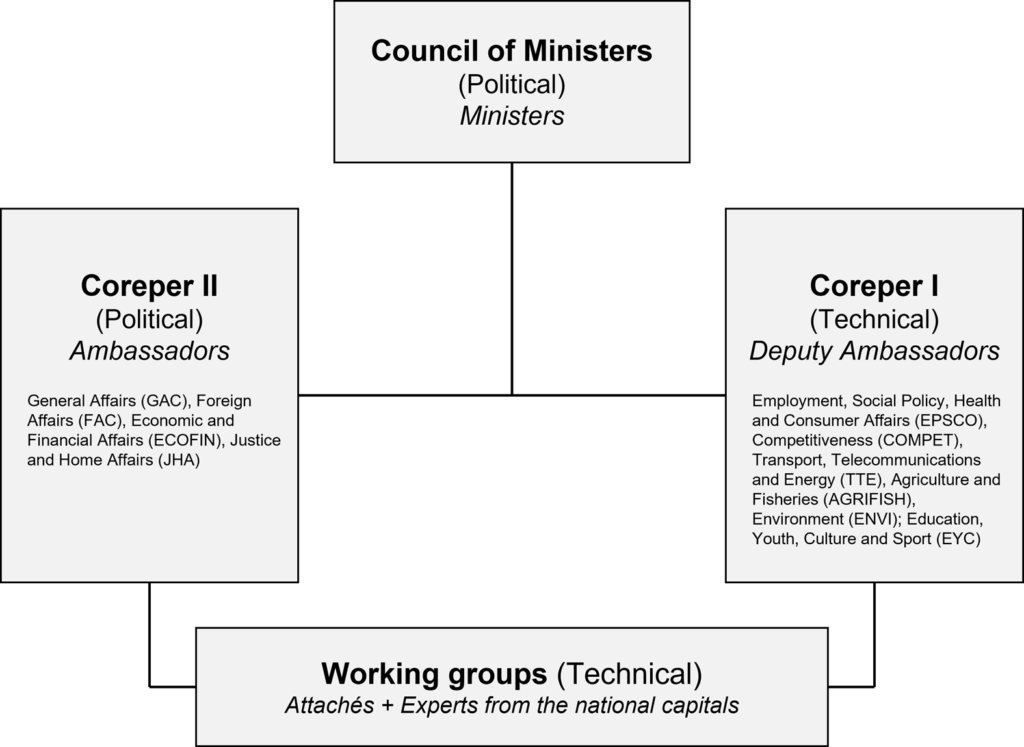

The ministerial meetings are prepared by the “Comité des Représentants Permanents” (short: Coreper). This is divided into Coreper I and Coreper II, depending on the thematic focus of the dossier. Contrary to expectations, the numbering of Coreper I and Coreper II has no hierarchical significance. On the contrary, Coreper II prepares the more important, political dossiers, while Coreper I prepares the work of the complementary, more technical Council formations. Each EU Member State is represented in Coreper by a Permanent Representative (Coreper II) and a Deputy Permanent Representative (Coreper I), who head the Permanent Representations (PermReps) of the Member States to the EU in Brussels and hold the status of ambassadors.

In reality, however, only about 15-20 percent of the agenda items are left to Coreper. The ministers themselves are left with only about 10-15 percent. It is the Council’s working groups, as the third instance of this negotiating staircase, that “pre-cook” about 70 percent of the decisions. In analysing and evaluating EU policy and intergovernmental impulses in the negotiation process, it is therefore essential not to focus initially on the bottleneck, but on the activities and interaction of the working groups responsible for the respective dossier.[2]

The institutional architecture of the Council of Ministers. Source: Author.

The Council working groups bring together so-called attachés, i.e. diplomats from the Permanent Representations of the Member States to the EU, who attend the meetings accompanied by experts from their respective capitals. The attachés, however, are usually not professional diplomats. While the Permanent Representatives and their deputies are seconded by the foreign ministries of their countries, the attachés of the working groups are instead seconded by the relevant national ministries, such as the ministry of health, finance, or education.

The PermReps can, however, be clearly distinguished from other diplomatic missions by the fact that the number of policy areas represented far exceeds that of a normal embassy. In principle, an EU health attaché represents all thematic areas of his or her health ministry, averaging 60-75 departments, about half of which produce EU-relevant results.

Large, old Member States have at least two attachés per Council configuration, while small, newer Member States are generally understaffed. This has corresponding implications for the negotiating position, mainly because EU diplomacy is generally different from traditional diplomacy: The Council is a legislative body; a thorough knowledge of the EU and national legal framework is therefore highly necessary and underlies the intensive acquisition of expertise. If this is the responsibility of only one individual, there is little time for informal rounds of negotiations and persuasion of one’s position.

The day-to-day work of an EU attaché in five roles

Information-gatherer, and -Provider

Attachés gather technical information in and about Brussels, especially on the position of other member states and the EU institutions on legislative proposals. The information gathered is channelled in the form of reports or written comments in a one-way street via the attaché to the capital, where it reaches the relevant officials, usually in the international/EU affairs departments of the respective ministry. The gathering and provision of information goes hand in hand with a filter function and prioritises which topics in the Brussels context are relevant for one’s own ministry.

Attachés of the newer Member States are additionally tasked with institutionalising communication between Brussels and their capital city in the first place, as there are still many ministries that are only marginally interested in the EU. In such cases, the influence of a Brussels attaché can be significant, as he or she has the ability to influence the substantive direction of the new engagement.

Networker and contact supplier

While ministries also have their own direct links to other Member States and to the Commission, which is especially true for the higher political levels, communication between Member States and the Commission usually always goes through the PermRep and thus the attachés. Thus, a large part of the attachés’ daily work consists of providing their colleagues in the national ministries with contact to the EU institutions or their counterparts in other Member States. Especially in crisis situations, rapid contact with a large number of states is necessary – for which the attachés are ideally placed. After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, officials in capitals quickly requested contact with their counterparts, asking their attachés in Brussels, for example, “Who can I contact in the French ministry, the Dutch ministry, the Austrian ministry, or the Italian ministry?”, etc.

Early warner

Proximity to both Member States and EU institutions makes attachés useful antennas for their capitals. In particular, close contact with the Commission – which, as the “guardian of the treaties,” monitors Member States’ compliance with EU commitments – ensures that any potential friction between the Commission and a Member States is quickly brought to the attention of the attachés, and thus to the capital: “When there is criticism, you hear it much more directly than in Brussels”. Apart from criticism to national policies potentially clashing with EU obligations,early warning also comes with legislative proposals initiated by the Commission. Given attachés’ consciousness of the national interests, they can report in advance a proposal that is contrary to national interests, enabling respective officials in the capitals to counteract these developments ex ante the publication of the proposal.

Representor and adviser

The attachés do not just pass on information, contacts and warnings to the capital. They are national delegates sent to Brussels with the mission of conveying and defending their country’s position in the best possible way. However, the discrepancy in shaping capacities was frequently emphasised by the attachés: While some even write their instructions themselves, others “wouldn’t even go to the toilet without the instructions from the capital”. In the Eastern European countries in particular, there is a long tradition of red lines; creative power is unwelcome.

Negotiator of draft legislation

Attachés, in conjunction with national experts, discuss “article by article, chapter by chapter” to identify where divergent interests need to be negotiated. Balancing divergent interests between Member States often translates into consistent bloc forming: first finding like-minded countries on a particular issue – either in formal or informal, multilateral or bilateral meetings, and then approaching those countries that are not like-minded in a united front. The majority wins.

In the ordinary legislative procedure, the European Parliament is co-legislator of the same dossier as the Council: the attachés thus often attend workshops and/or conferences organised by members of the EP on issues related to the dossier, which is a strategic opportunity for both sides. Frankly, “You go there and say something for five minutes about how important the issue is, which in turn allows us to ask for reciprocity later in the trialogue, for example, when we need help convincing colleagues of the importance of a particular article”.

Recommendation and outlook

While stakeholders in legislative processes involving the Council of Ministers either focus directly on the ministerial level but at least on Coreper as the bottle neck and decision maker, this first insight into the structure and daily work of the working groups has shown: It is much more sensible to first get an idea of what issues and challenges are already being pre-cooked at the working group level in order to make one’s point of view heard and translated. This is especially true in light of the fact that the EU-27 attachés, based on their day-to-day interactions, are driven by a political commitment to collaborate and find solutions, which impacts their roles as representatives and advisors, as well as national negotiators on draft legislation to the detriment of their capitals. A following article will thus address the socialisation processes within the Council working groups and beyond, answering, among other things, why, for instance, the Permanent Representatives in Brussels are especially in Berlin more often called “Ständiger Verräter” (eng: permanent traitor) instead of “Ständiger Vertreter” (eng: permanent representatives).

[1] An overview of the policy areas in which the Commission can legislate “exclusively”, “shared”, or “supportively” can be found here.

[2] An overview of all the Council’s working groups can be found here.