What the end of Twitter would mean for public relations – a scenario

The takeover by Elon Musk is shaking Twitter permanently and moving the company in a dangerous direction – but what would the end of the social network mean for our debates and how must politics and business adjust to the new situation?

When the takeover of Twitter by Elon Musk came about after a long back and forth, many employees and users did not foresee anything good. However, at the latest when the billionaire marched into the headquarters in San Francisco armed with a sink, it was clear that from now on different times would dawn for the influential network.

Since then, events have been unfolding at a rapid pace. Numerous accounts of right-wing agitators, conspiracy theorists and other radicals have been unblocked, the level of racist and inflammatory tweets has risen and accounts critical of Musk, including those of journalists, have been blocked. The consequences: Major advertisers are cancelling their ads, institutions are reviewing their involvement in the network and users are withdrawing if they don’t close their accounts right away.

Musk finally practised damage limitation when he let the users of his network vote on his resignation and then declared it. So far, however, few believe that this will diminish his influence on Twitter. If the developments continue, there are serious doubts as to whether Twitter will survive. Two scenarios would then be conceivable:

- Twitter goes bankrupt because neither the new pay features generate enough revenue nor the advertisers come back.

- The network becomes so toxic politically and socially that further engagement would only be possible for players clearly to the right of centre without reputational damage.

It is not yet foreseeable whether Twitter will end up in one of the two scenarios. But organisations with a presence in the political and media space should start planning for that scenario.

But why should we even care whether Twitter exists or not? It is not among the top 3 social networks in Germany and less than 20% of citizens use it at all. Both are true. But Twitter sets three things apart compared to the other social networks:

- It has very low barriers to entry because it is primarily text communication and thus requires minimal education as well as hardware.

- It has high speed. News (last example: missiles hitting a Polish border town) always appears first on Twitter and is commented on and classified here within minutes, if not seconds. Debates develop very quickly, not always to everyone’s delight (#shitstorm).

- Twitter has a strong concentration of the politics and media “bubble”. According to a 2015 study, almost every 4th user was a journalist – this may not be quite so extreme anymore, but Twitter is still the social network of choice among journalists. According to the portal pollytix, 80 percent of members of the Bundestag have a Twitter account. This concentration means that debates on Twitter often have a higher external reach and penetrating power, as their multipliers (politicians and journalists) are more aware of them.

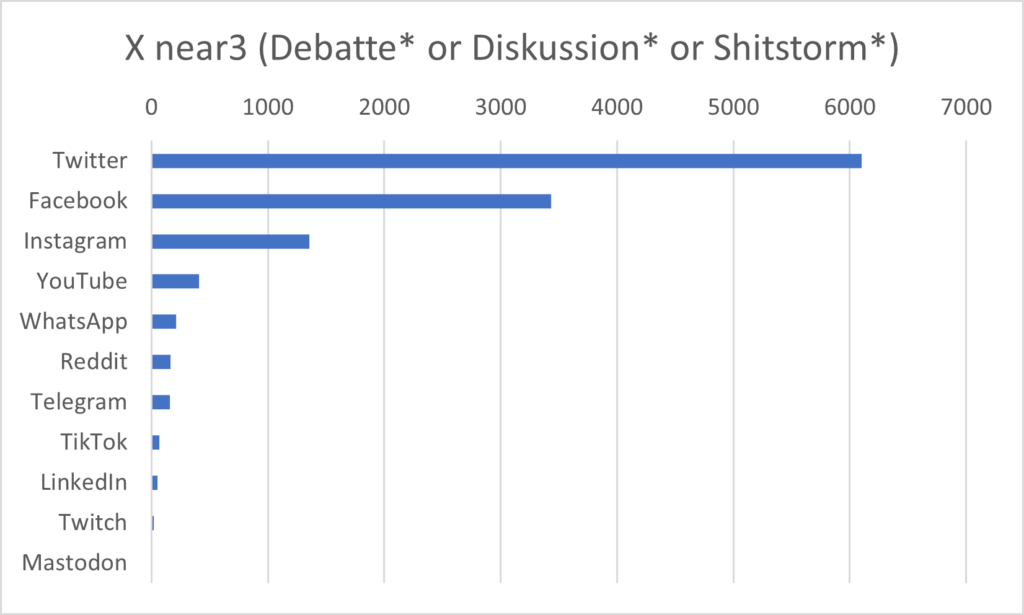

These three characteristics have meant that many of the social debates have not only been conducted on Twitter, but the momentum has also often come to public attention via Twitter (#meToo, #IamHanna). Quite a few would argue that Twitter made Karl Lauterbach the health minister. An example of this can be found by searching media databases for social networks in combination with terms such as debate, discussion or shitstorm. Twitter is the undisputed leader here and is cited more often than the next 3 networks combined.

This relevance has also led to almost all large and not so large German companies having one or more accounts on Twitter. This is not about customer communication, but about visibility among journalistic as well as political stakeholders.

An end to Twitter therefore means not only the end of a company, but also the end of the central digital debate space in Germany and other countries.

The debate will fragment – at least for several years to come

Fearing the end of Twitter and looking for alternative exchange formats, numerous politicians and social influencers are already opening accounts with the competitor Mastodon or founding their own groups in so-called “dark socials” like Telegram or Whatsapp. We thus see the beginnings of a fragmentation of the public debate, in two respects:

On the one hand, the choice of an alternative social network is definitely also one of political colouring. Business-savvy actors mainly switch to LinkedIn, others prefer decentralised networks like Mastodon. Those who are not afraid of the camera go to Instagram and TikTok. So the debate is no longer between different perspectives, but much more internally between individual currents.

On the other hand, there is a tendency to switch to platforms that exclude debate from the outset. Newsletters, Telegram or WhatsApp primarily enable one-way communication; comments and counter-opinions are often technically not provided for – but perhaps also unwanted. The well-rehearsed sequence of event, Twitter debate and subsequent media coverage would then no longer be possible in its current form.

This fragmentation will lead to a prolonged phase of uncertainty: For the senders, it will first have to become clear on which channel which target group can be reached and what the target group-specific content must look like. On the recipient side, a similar problem will arise. In addition, it will be much more difficult for actors to understand the position of stakeholders if they have to monitor various platforms and, if they want to participate in the debate, they will also need their own expertise.

Gathering information will become more time-consuming

Twitter has always been a good seismograph, precisely because the concentration of relevant stakeholders was so high here. If the debate fragments into other networks and platforms, the effort to position oneself vis-à-vis stakeholders, to get in touch with them or to identify critical debates at an early stage is much higher.

Monitoring multiple platforms is of course nothing new. However, it is more elaborate and in some cases (e.g. LinkedIn) can only be reliably guaranteed manually. Above all, the collected information must be brought together for a 360° view. While there is a broad tool ecosystem around Twitter that makes monitoring possible even for small budgets, tools that cover several platforms are usually much more expensive and also more complex. The fragmentation therefore significantly increases the effort for monitoring, not only in a monetary sense, but also in terms of technical skills.

But it is not the only effort that increases. Twitter also formed a kind of “Reputationsschufa” in Germany. Unlike in the USA, follower numbers were never a currency in themselves. Seen in context, however, they were certainly a factor in assessing reputation and trust in an actor. Especially when moving in unfamiliar subject areas, they were an easy way to identify influential actors. Interestingly, it was also always a good indicator of local and regional politicians’ ambitions whether they had an active Twitter account.

Many journalists also used Twitter extensively to find sources. It is surprising how many quotes in articles nowadays do not come from requests or interviews, but are “pulled” directly from Twitter. That is why there are quite a few voices that would welcome an end to Twitter from the point of view of journalistic quality. The focus on the platform has narrowed the view, because as well as the “Berlin bubble” is represented, many population groups are not. For journalists, their own information gathering would also become more difficult if Twitter no longer existed.

However, this is not only an issue for them – placing quotes will also become more difficult without Twitter. Especially niche actors could find a journalistic hearing via Twitter through clever comments or strong positioning that they probably would not have received without this platform. If Twitter ends, this could favour thematic “top dogs”, as the effort to find alternative actors and get in touch may not be possible for journalists in short-staffed and tightly scheduled editorial departments.

Consequences

Whether Twitter will continue to exist in its current form can neither be affirmed nor denied at this point in time. But it is a fact that the cards will be reshuffled with the new ownership and an end seems quite possible. But how can organisations that have been active on Twitter so far prepare for this? In our view, there are three measures that will help in the short term:

Those who have well-structured and up-to-date stakeholder overviews should check again whether they also include alternative networks and other contact data for Twitter. However, since in practice it is often the case that the creation and maintenance of these overviews do not have the highest priority, now would be a good time to create and fundamentally overhaul them. If it is known which stakeholders are relevant for one’s own topics, these should not only be monitored thematically, but also with regard to possible announcements of platform changes. A good technical infrastructure helps here; recommendations can be found, for example, in our Tech Landscape Politics & Communication.

Those who have used Twitter to place their own topics and get in touch with journalists should invest resources in traditional media work. Building and maintaining personal relationships to become part of the relevant debates will experience a renaissance in this scenario. Especially for actors who do not have a high profile, it is essential to be networked with journalists who are thematically relevant to them. However, relying on personal relationships alone will not be sufficient. If Twitter is no longer used, a high degree of creativity and courage is required to find new ways to place one’s own message in the public eye.

Lastly, many organisations have invested time and resources in building their Twitter audiences. These are often not small sums over the years. When Twitter ends, this investment has to be written off. It should therefore be considered in good time whether it makes sense to try to mobilise followers on alternative platforms (other social networks, newsletters, etc.). This decision should be derived from one’s own corporate and PR strategy and should be well prepared. But: These considerations should be made now. Since the situation is very dynamic, it may be necessary to react very quickly. Those who only then enter the analysis and decision-making process will not be able to save the investments made.