Buy now, pay later (BNPL) is booming. Best known in Europe is Klarna with 90 million active consumers, shopping at 250,000 merchants in 17 countries, processing 2 million transactions a day. Klarna’s one-click payment services and instalment plans have benefitted from technological innovation, changing customer behaviour and the pandemic, acting as a catalyst for online shopping and digital payments around the globe. The stupendous growth and success have made Klarna Europe’s most valuable fintech at a valuation of $45.6 billion. Other notable BNPL companies include Affirm or Afterpay, with PayPal entering the market by acquiring Japanese Paidy.

Buy now, pay later services are growing at a rate of 39 percent per year and expected to exceed $260 billion by 2025, arguably turning “consumer finance on its head”.

Buy now pay later schemes do exactly what it says – online shoppers can buy what they need or crave for without having to pay for it until a later date. While offers and business models vary slightly, payment is usually made through regular interest-free instalments or after an interest-free deferral period. Purchases at relatively small amounts such as for fashion items, are usually paid back within a few weeks. BNPL payments methods have particularly gained popularity among young and new-to-credit customers, such as millennials and Gen Z consumers who lack credit history and whose disposable income is smaller.

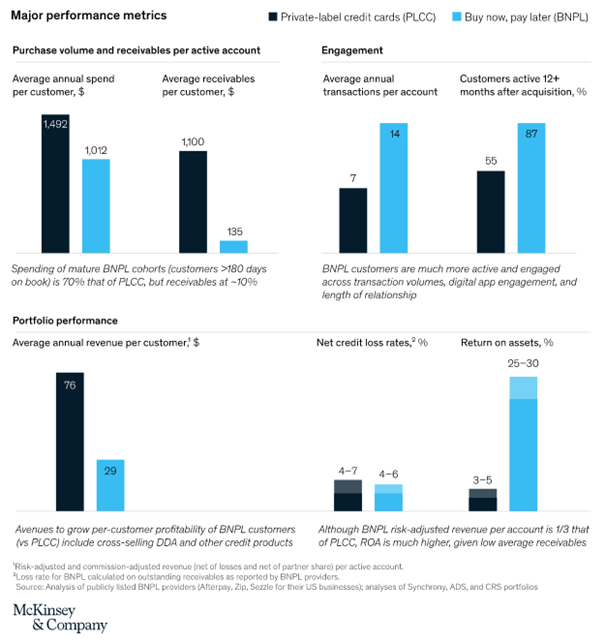

In a recent report McKinsey has compiled metrics to demonstrate why BNPL is becoming such an attractive business model.

While ever more consumers embrace BNPL’s undisputed convenience, and retailers benefit from higher conversion rates, it has also caused uneasiness in terms of consumer protection and called regulators to action. With steep costs of late or missed payments alongside a general concern regarding increasing over-indebtedness in times of financial uncertainty, BNPL is suspected of effectively normalising overspending by consumers who may not be able to afford it.

The focus of the regulators across the globe, and in particular the UK and the EU, has been drawn to BNPL, as “one common feature of BNPL products is that they typically avoid the level of regulation applied to traditional consumer lending, and appear to be specifically designed to achieve this”, as Fitch Ratings has recently put it.

Consumer credit regulations indeed provide exemptions enabling such avoidance strategies to be put in place. These ‘loopholes’ usually revolve around the amount of credit, with smaller tickets not being caught by otherwise stringent obligations, the duration of the credit, with shorter periods not covered and the costs, i.e. the interest rates charged, which at initially zero help escape the regulatory framework.

But regulators are now zooming in and taking action. In the United Kingdom, the government earlier this year announced its intention to bring unregulated interest-free BNPL products into regulation given the potential risk of consumer detriment. On 21 October 2021 a consultation has been launched, setting out potential policy options to achieve regulation of BNPL. The consumer detriment is characterised by the UK government as comprising of

- how the product is promoted to consumers and presented as a payment

option; - misunderstanding of the product by consumers, including the absence of

information given to consumers about the features of the agreement; - the absence of any requirements to undertake creditworthiness

assessments; - the potential to create high levels of indebtedness;

- inconsistency of treatment of customers in financial difficulty; and,

- impacts on the wider credit market including little visibility of BNPL debts

on an individual’s credit file.

While the consultation will last into early 2022 and emphasises the need for a proportionate approach to be taken, it is widely expected that subsequent measures will effectively end the ‘unregulated status’ of BNPL.

In response, Klarna has already announced changes to its services in the UK. Klarna will introduce new wording to make it “absolutely clear” to customers that they are being offered credit, with penalties for missed payments. It has also added a “pay now” option alongside its offers to spread payments over several weeks or months. Other promises include “stronger credit checks” and allowing customers the possibility to share their account’s income and spending data via the UK’s open banking infrastructure to prove they can afford repayments. Additionally, Klarna has removed late fees from its longer-term repayment plans of six months and over.

The European Union has meanwhile moved beyond the stage of consultation as the Commission has tabled a legislative proposal to update the present regulatory framework for consumer credits. The Proposal for a Directive on consumer credits sets out to close the ‘loopholes’ across credit amounts, repayment periods and ‘interest-free’ agreements.

Article 2 of the proposal sets out the scope of the Directive, which covers certain credit agreements for consumers and crowdfunding credit services. Some exemptions so far permitted by Article 2 are to remain valid, whereas it is envisaged to remove those concerning

- minimum amounts,

- overdraft facilities,

- free interest rate,

- credit without charges or

credit to be repaid within 3 months with only insignificant charges.

In the accompanying Impact Assessment, the European Commission states that “the situation of consumers under the impression of having unlimited credit possibilities from the moment they pay back a part of their debt every month, can suddenly become unsustainable because of high costs non-transparently disclosed. These credits frequently amount to less than €200, and are hence exempted from the [current] Directive’s obligations.”

The inclusion of currently exempted products such as BNPL in the scope of the Directive is expected to improve creditworthiness assessments. The lender would be subject to the obligation to perform an assessment of the potential borrower’s creditworthiness before granting credit, and more precise requirements on how to assess consumer creditworthiness would become applicable.

It would seem that creditworthiness checks, alongside obligatory pre-contractual information and provision of information at the advertising stage do not sit well with a business model that relies on instant provision of what until now was not considered ‘credit’ in the regulatory sense.

The legislative procedure between the European co-legislators is still at an early stage, with the proposal only having been published just before the summer recess. The European Parliament is expected to start debating the proposal in the Committee on Internal Market and Consumer Protection (IMCO) and the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON) within the next few weeks. Initial exchanges among the Member States within the Council’s Working Party on Consumer Protection are ongoing.

If you have further questions on BNPL and the EU consumer credit regulation review in general do not hesitate to contact Florian Lottmann and Elisabeth von Reitzenstein at our Brussels office.